Celebrating all the mamas

Honor all the working women who came before us

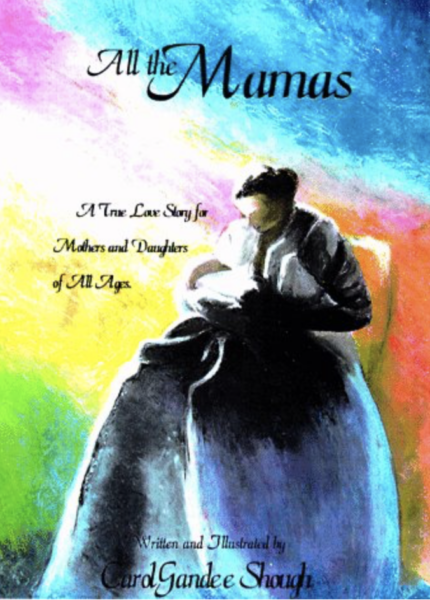

“All the Mamas,” by Carol Gandee Shough is one of my favorite children’s books of all time. While my own daughter was a toddler, it was published in 1998. I used to read it to her all the time and to this day, my daughter cherishes that book. In this book, Carol Shough, tells the story of her mama to her daughter, and then her mama’s mama, and so on, all the way back throughout her ancestral linage.

It serves both as a simple history book but more to remind us that we are here because of all the mothers from across time. Our role as women in the workforce, and the independence it gives us, is not simply because of our own mother, but because of all the mothers that came before her. I searched for this book today to link it in the show notes, but it seems to be out of publication. There are used versions on Amazon, but it is a rare find these days. That is too bad, because it is a beautiful story and a wonderful way to honor our mothers – all our mothers.

Persistent working women cleared a path for us

As one high achieving women among so many, I thought Mother’s Day would be an excellent day to take a moment to celebrate all the women who came before us, to honor the lineage of strong, intelligent, persistent women who have cleared the path that allows us to be who we are today.

Women in the workforce from the earliest times

Women have worked at agricultural tasks since ancient times, and continue to do so around the world. The Industrial Revolution, which occurred roughly between 1760 and 1840, changed the nature of work in Europe and other Western countries. The Industrial Revolution marks a major turning point in history; almost every aspect of daily life was influenced in some way. We all remember our elementary history classes about steam engines and cotton gins, that increased production.

The Industrial Revolution also helped to spread knowledge through printing presses that allowed for more rapid printing of books. Working for a wage, and eventually a salary, became part of urban life. Initially, women could be found doing the hardest physical labor, including hauling heavy coal carts through mine shafts in Great Britain, a job that also employed many children. This ended after government intervention and the passing of the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842, an early attempt at regulating the workplace.

Working women putting in hard labor

During the 19th century, an increasing number of women in Western countries took jobs in factories, such as textile mills, or on assembly lines for machinery or other goods. Women also peddled produce, flowers, other marketable goods, or raised small animals and produced needlepoint pieces for manufacturers. Working-class women were usually involved in some form of paid employment, as it provided some insurance against the possibility that their husband might become too ill or injured to support the family. During the era before workers’ compensation for disability or illness.

In the early 1900s, employers stated they preferred to hire women, because they could be “more easily induced to undergo severe bodily fatigue than men”. Childminding was another necessary expense for many women working in factories. Pregnant women worked up until the day they gave birth and returned to work as soon as they were physically able. In 1891, a law was passed requiring women to take four weeks away from factory work after giving birth, but many women could not afford this unpaid leave, and the law was unenforceable.

Busting myths about women in the workforce

The 1870 US Census was the first United States Census to count “females engaged in each occupation” and provides an intriguing snapshot of women’s history. It reveals that, contrary to popular belief, not all American women of the 19th century were either idle in their middle-class homes or working in sweatshops. Women were 15% of the total work force (1.8 million out of 12.5). They made up one-third of factory workers, but teaching and the occupations of dressmaking, millinery, and tailoring played a larger role. Two-thirds of teachers were women. Women could also be found in such unexpected places as iron and steel works, mines, sawmills, oil wells and refineries, gas works, and charcoal kilns, and held such surprising jobs as ship rigger, teamster, turpentine laborer, brass founder/worker, shingle and lathe maker, stock-herder, gun and locksmith, and hunter and trapper.

Educating women in the workforce and World War I

In the beginning of the 20th century, women were regarded as society’s guardians of morality; they were seen as possessing a finer nature than men and were expected to act as such. Their role was not defined as workers or money makers. Women were expected to hold on to their innocence until the right man came along so that they can start a family and inculcate that morality they were in charge of preserving.

The role of men was to support the family financially. Yet at the turn of the 20th century, social attitudes towards educating young women were changing. Women in North America and Western Europe were now becoming more and more educated, in no small part because of the efforts of pioneering women to further their own education, defying opposition by male educators. By 1900, four out of five colleges accepted women and a whole coed concept was becoming more and more accepted.

In the United States, World War I made space for women in the workforce, among other economical and social influences. Due to the rise in demand for production from Europe during the raging war, more women found themselves working outside the home.

“The American Woman … has lifted her skirts far beyond any modest limitation”

~The New York Times, July 1920

In the first quarter of the century, women mostly occupied jobs in factory work or as domestic servants, but as the war came to an end they were able to move on to such jobs as: salespeople in department stores as well as clerical, secretarial and other, what were called, “lace-collar” jobs. In July 1920, The New York Times ran a head line that read: “the American Woman … has lifted her skirts far beyond any modest limitation,” which could apply to more than just fashion; women were now rolling up their sleeves and skirts and making their way into the workforce.

WWII drove women to the workforce by the millions

World War II created millions of jobs for women. Thousands of American women actually joined the military: the Women’s Army Corps (United States Army) WAC; the Navy (WAVE); Marines; Navy Nurse Corps and the Coast Guard. Although almost none saw combat, they replaced men in noncombat positions and got the same pay as the men would have on the same job. At the same time over 16 million men left their jobs to join the war in Europe and elsewhere, opening even more opportunities and places for women to take over in the job force.

Although two million women lost their jobs after the war ended, female participation in the workforce was still higher than it had ever been. In post-war America, women were expected to return to private life as homemakers and child-rearers. Newspapers and magazines directed at women encouraged them to keep a tidy home while their husbands were away at work. These articles presented the home as a woman’s proper domain, which she was expected to run. Nevertheless, jobs were still available to women. However, they were mostly what are known as “pink-collar” jobs such as retail clerks and secretaries.

The Quiet Revolution: The independent female is born

The increase of women in the labor force of Western countries gained momentum in the late 19th century. At this point women married early on and were defined by their marriages. If they entered the workforce, it was only out of necessity.

Phase 1

The first phase of the quiet revolution encompasses the time between the late 19th century to the 1930s. This era gave birth to the “independent female worker.” From 1890 to 1930, women in the workforce were typically young and unmarried. They had little or no learning on the job and typically held clerical and teaching positions. Many women also worked in textile manufacturing or as domestics. Women promptly exited the work force when they were married, unless the family needed two incomes.

Phase 2

Towards the end of the 1920s, as we enter into the second phase, married women begin to exit the work force less and less. Labor force productivity for married women 35–44 years of age increase by 15.5 percentage points from 10% to 25%. There was a greater demand for clerical positions and as the number of women graduating high school increased they began to hold more “respectable”, steady jobs. This phase has been appropriately labeled as the Transition Era referring to the time period between 1930 and 1950. During this time the discriminatory institution of marriage bars, which forced women out of the work force after marriage, were eliminated, allowing more participation in the work force of single and married women.

Additionally, women’s labor force participation increased because there was an increase in demand for office workers and women participated in the high school movement. However, still women’s work was contingent upon their husband’s income. Women did not normally work to fulfill a personal need to define ones career and social worth; they worked out of necessity.

Phase 3

In the third phase, called the “roots of the revolution,” which encompassed the time from 195 to the mid-to-late 1970s, the movement began to approach the warning signs of a revolution. Women’s expectations of future employment changed. Women began to see themselves going on to college and working through their marriages and even attending graduate school. Many however still had brief and intermittent work force participation, without necessarily having expectations for a “career”. To illustrate, most women were secondary earners, and worked in “pink-collar jobs” as secretaries, teachers, nurses, and librarians. The sexual harassment experienced by these pink collar workers is depicted in the film 9 to 5. Although more women attended college, it was often expected that they attended to find a spouse—the so-called “M.R.S. degree”. Nevertheless, Labor force participation by women still grew significantly.

Phase 4

The fourth phase, known as the “Quiet Revolution”, began in the late 1970s and continues on today. Beginning in the 1970s women began to flood colleges and grad schools. They began to enter profession like medicine, law, dental and business. More women were going to college and expected to be employed at the age of 35, as opposed to past generations that only worked intermittently due to marriage and childbirth. This increase in expectations of long-term gainful employment is reflected in the change of majors adopted by women from the 1970s on.

The percentage of women majoring in education declined beginning in the 1970s; education was once a popular major for women since it allowed them to step into and out of the labor force when they had children and when their children grew up to a reasonable age at which their mothers did not have to serve primarily as caretakers. Instead, majors such as business and management were on the rise in the 1970s, as women ventured into other fields that were once predominated by men.

They experienced an expansion of their horizons and an alteration of what it meant to define their own identity. Women worked before they got married, and since women were marrying later in life, they were able to define themselves prior to a serious relationship. Research indicates that from 1965 to 2002, the increase in women’s labor force participation more than offset the decline for men.

The Pill’s impact on Women in the Workforce

The reasons for this big jump in the 1970s has been attributed to widespread access to the birth control pill. While “the pill” was medically available in the 1960s, numerous laws restricted access to it. Case law began to change this with decisions such as those in Griswold v. Connecticut in (1965) which overturned a Connecticut statute barring access to contraceptives and Eisenstadt v. Baird in1972, which established the right of unmarried people to access contraception. By the 1970s, the age of majority or the threshold of adulthood as recognized in law, had been lowered from 21 to 18 in the United States. This was largely as a consequence of the Vietnam War.

The change in age of majority also affected women’s right to effect their own medical decisions. Since it had now become socially acceptable to postpone pregnancy even while married, women had the luxury of thinking about other things, like education and work. Other changes between 1950 to the 1970s included the electrification of “women’s work” around the house. Household tasks became easier, leaving women with more time to dedicate to school or work. Due to the multiplier effect, even if some women were not blessed with access to the pill or electrification, many followed the example of the other women entering the work force for those reasons. The Quiet Revolution has not been a “big bang” revolution; rather, it happened — and is continuing to happen — gradually.

Firsts for Working Women

In the 1980’s there were a lot of political and workforce firsts for women that were examples of how rapidly things would improve in the 1990s and 2000s: Sandra Day O’Conner was sworn in as the first Female Supreme Court Judge. Sally Ride became the first woman astronaut in space, Geraldine Ferraro was the first woman nominated as a VP candidate. In the 1990s, Janet Reno became the first woman Attorney General, and Madeleine Albright became the First woman Secretary of State. By 2016, we had the head of a major political party nominate a woman for their candidate in the general election for President of the United States, Hillary Clinton. These are all signs that we are moving in the right direction.

Still, here we are in 2020, and there are still pay gaps between women and men. Within most large organizations, the executive level and the CEO are still men. Female CEOs make up only 5% of Fortune 500 companies today. Even the executive and VP level shows over only 29% of those positions are women. This is true in the organizations I work in now, which are military organizations. Yes we still have a LONG way to go, but we ARE moving in the right direction.

We have all the bold women who fought for their rights. They were not only fighting for themselves, they were fighting for all of us. Ladies – we have almost limitless options available to us today, beyond anything I could have imagined as a teenager and certainly beyond everything my great grandmother could have dreamed for her granddaughters and great grand daughters beyond her. Today, I celebrate my own mother for being brave and strong and for giving me a direct, relatable example of what success looks like. I also celebrate all the mamas before her for clearing the path so that we are all free to become the best that we can be.

Activity for thought and improvement:

This week I want you to remember one woman who helped you get to where you are today and take some time to tell her how much you appreciate her. I can think of one woman who probably doesn’t know what an effect she had on me. Her name is Mrs. Barb Keenan, in Fort Morgan Colorado. She was my AP History teacher in high school during my Senior year. I was having a hard time, due to my family situation and my high school boyfriend, and as a result I was on a path to failing her class. She could have let me fail, she could have had me reclassified into an easier class. The thing is, she knew I was smart enough to be in the class, and she probably realized there was something underlying the reason for my slipping grades.

She pulled me aside one day and asked to come see her after class. That afternoon, she talked to me like a human, not like a student who was failing her class. I told her what was wrong, and she listened for a really long time. Then she said, here is what we are going to do. She pulled a book out of her drawer and handed it to me. It was titled, “The Hessian” by Howard Fast. The Hessian tells the story of the capture, trial, and execution of a Hessian drummer boy by Americans during the Revolution. (I remember it to this day.)

She told me to read it and then she gave me an assignment to write a paper about it. (I also needed to turn myself around and keep up with the future assignments.) She said if I did this, I would not fail her class. I kept my part of the bargain, and so did she. What that led to was hope that things would get better. It also impacted who I have become as a working woman and a leader now that I am in situations where I can impact people’s lives.

I would love to hear about women who have made a difference in your life. Tell your story to your voice recorder on your phone and e-mail me the file to tami.north@genuinedrivenwomen.com. I will share your story on the podcast and you will inspire others!